An exhibition at The White Horse in 2011 over the weekend of Heritage Open Days.

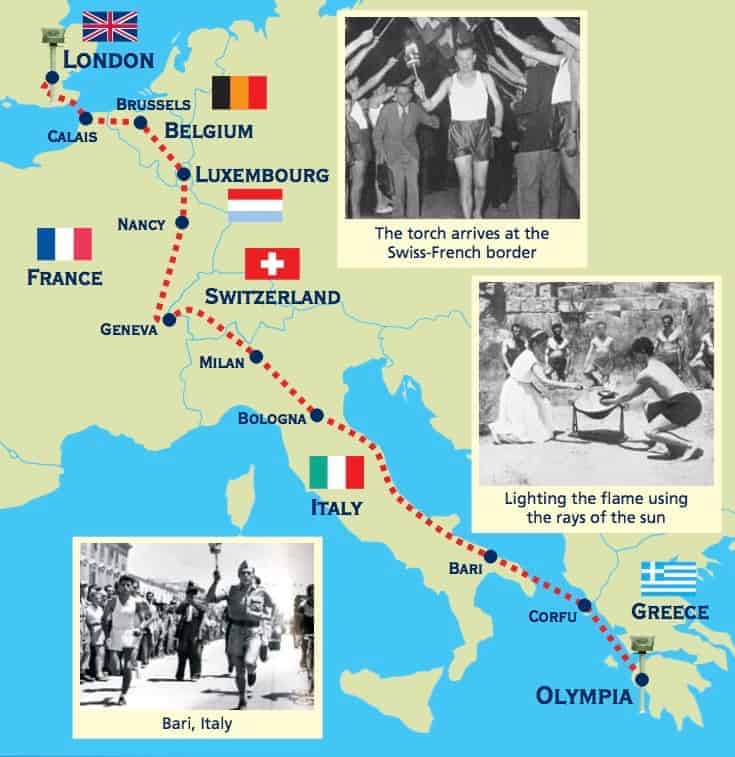

1948 Olympic Torch Relay

“The important thing is not winning but taking part. The essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well”

Baron de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic movement.

The Austerity Games

London was supposed to hold the 1944 Olympic Games but due to the Second World War, they were cancelled. In 1948, the question was whether Britain could host such an event when the country was in the grip of rationing and privation, its cities devastated by bombing and its people wearied by war. Clothes, food, petrol and building materials were still on the ration: how could post-war Britain manage?

Lord Burghley, chairman of the British Olympic Council, was sure we could do it. A committee was set up to work out the details and, after several meetings, they recommended that the Lord Mayor of London should apply to host the Games. The budget was £730,000.

The Opening Ceremony

The Games were opened on the 29th July by King George VI. Over 4,000 athletes were present, representing 59 nations. Germany and Japan were excluded and the USSR abstained.

More than 40,000 people packed the Empire Stadium in Wembley to see the opening ceremony, which was a simple affair compared with modern extravaganzas. There was a 21-gun salute and thousands of homing pigeons were released to symbolise culture and peace across the world.

Running the Games

All the venues were already in existence. No Olympic village was built: foreign athletes were accommodated in military camps and London colleges while London-based athletes were expected to live at home. Competitors did get increased food rations (5,467 calories a day rather than the usual 2,600) but some of this food was contributed by countries taking part and the American team had fresh food flown in daily. British athletes had to make or buy their own kit.

America topped the medals table, wining 84 in total. Britain gained a respectable 23, including three golds. The Games even made a profit of £29,420 (on which £9,000 was paid in tax).

Relay for Peace

This was the second Olympic torch relay in modern times. The first was at the 1936 Games in Germany. Nazi propagandists came up with the idea of lighting the torch at the ancient Olympian site in Greece and then running it to the Games, projecting an image of the Third Reich as a modern, powerful state and hijacking the Classical past as an ‘Aryan’ forerunner of the new Germany.

In 1948, the world was very different. The European leg of the torch relay passed through countries ravaged by war, particularly Greece and Italy. The first runner removed his uniform to reveal running kit underneath, thus symbolising the peace that reigned during the Ancient Greek games. Frontier regulations were relaxed to allow the flame through.

After long years of apparently almost unending national and international strain and stress, here was a gleam of light, the light of a Flame, which crossed a continent without hindrance, which caused frontiers to disappear in its presence, which gathered unprecedented crowds to see it pass in city, town and village, and which lit the path to a brighter future for the youth of the world… from the official 1948 Olympics report.

The Relay Reaches Dorking

About 4,000 people crowded Dorking High Street on the morning of Thursday, 29th July to see the Olympic torch relay.

The handover between John Williams and Ted Henton took place outside the White Horse Hotel at 8.22 am. Each stage between Betchworth, Dorking and Westcott took about fifteen minutes; each runner could only jog along as the police and AA escorts tried to push through the spectators filling the roadway.

Both men were from the Dorking St Paul’s Athletic Club. John Williams had been a fine sprinter, tipped for the (cancelled) 1940 Helsinki Olympics. A leg wound sustained during the Italian campaign ended his running career. Ted Henton had been one of the first boys to join the club in 1935 and was now its Captain. Both men fulfilled the stipulation of the 1948 Olympic Organising Committee, which asked for young men “of good physique and physical fitness to represent the youth of Britain”.

After the relay, Williams’s torch was passed from hand to hand among the crowd. An excited group of children on bicycles accompanied Henton to Westcott where, after the next handover, his torch was used to light a woman’s cigarette. The enthusiasm of Dorking people made the event an immense success.

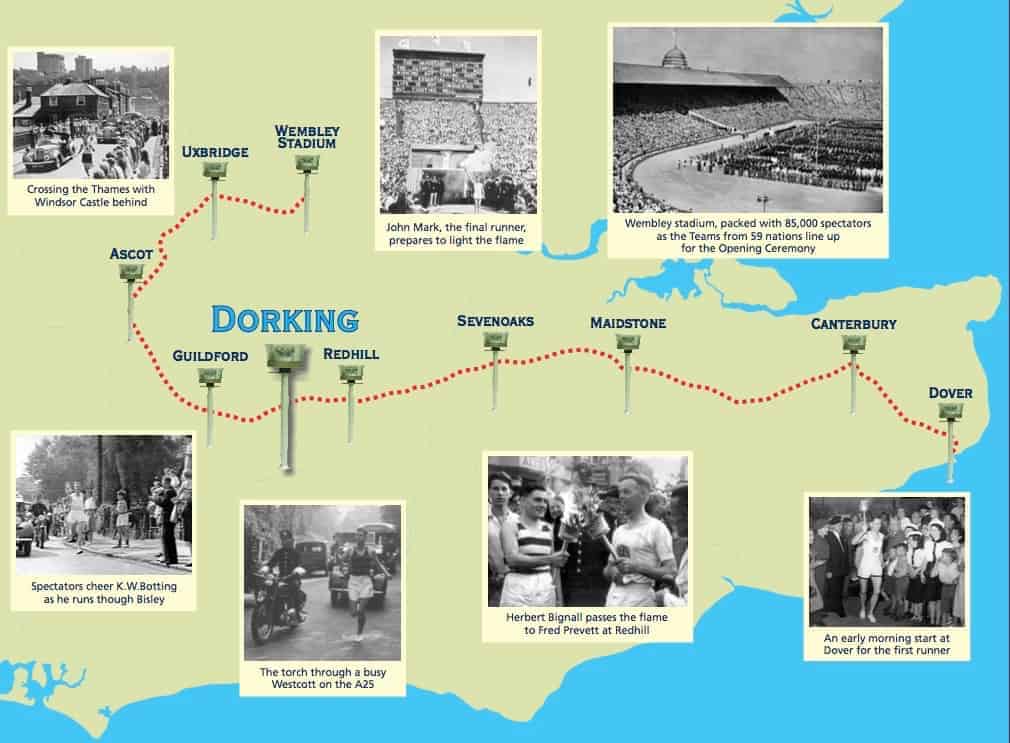

Walter Wareham

The Clerk of the Course for athletics was Walter Wareham, Dorking schoolmaster and founder of the Dorking St Paul’s Athletic Club. He had to check all the course measurements, oversee the ground staff as they set out the lanes and ensure all the equipment was ready. Most of all, he had to gather the athletes and make the draw before each race. He obviously enjoyed meeting the great sportsmen of the day.

“To see them keyed up and reacting just like any other athlete of a humble club; to jest with them and hear their expressions of joy when winning.”

Wareham did an excellent job and was complimented on the superb standard of the track. He spoke some French and German but otherwise used an interpreter to speak to the athletes and the International Jury who monitored everything he did. Organising the Decathlon proved the most difficult, with the last race starting in darkness at 10.20 pm.

“I shall always remember the complete friendliness of all the athletes, their fine sportsmanship, the utter lack of anything that could be called ‘an incident’, their handshakes with one another before the events.”