By 1917 the population had endured nearly three years of war. As the nation’s resources were directed towards the war effort civilians suffered shortages. A Ministry of Food was established to prevent hoarding and profiteering, and to encourage the population to consume and waste less.

But Britain was dependent on imports for 60% of foodstuffs which made the country vulnerable when German submarines began to target shipping. By March 1917 it was estimated that the country had only enough food to last 6 weeks.

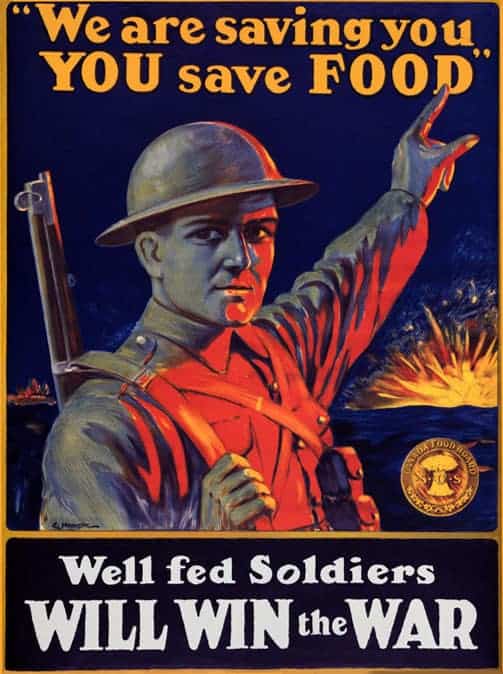

Ministers read out food orders from their pulpits; schools provided ‘war-time’ recipes, and cookery classes were held in village halls. The Urban District Council procured allotment sites so that people could grow food, and schoolboys from the Dorking British School were sent to tend the allotments of serving soldiers in order to maintain production. Women were recruited to work in the fields, and in Newdigate farmers were instructed to kill sparrows that were damaging crops. Even so, by 1918 the prospect of being unable to bring in harvests due to lack of manpower threatened mass hunger. Dorking High School sent boys off to help with the harvest on farms in Wiltshire and younger children scoured the hedgerows for edible fruit.

Shortages and fatigue took a toll on health and morale. Schools were particularly affected with many closed for weeks at a time because of teacher shortages, repeated bouts of contagious disease, and a lack of fuel to fire the heating stoves.

Rationing of sugar, meat, flour, butter, margarine and milk began in 1918. But having a ration card did not necessarily mean that householders could obtain rationed goods – grocers often favoured wealthier customers who were able to buy other foodstuffs, over those who could not, when supplies came in. And many people could not afford to buy what was on the ration: the local paper called for offal and bones to be sold without coupons to alleviate the hardship of poorer families.

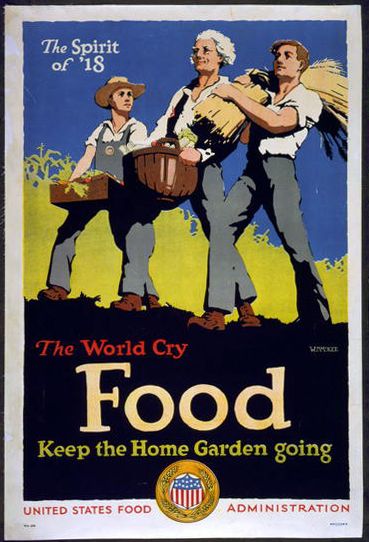

Poster encouraging the civilian population to keep food production going. The Urban District Council made great efforts to secure allotments and to keep the allotments of serving men tended. Local landowners made land available for villagers to grow food and the Duke of Norfolk allowed some to take wood for fuel from Holmwood Common when coal and coke supplies ran low and prices rose.

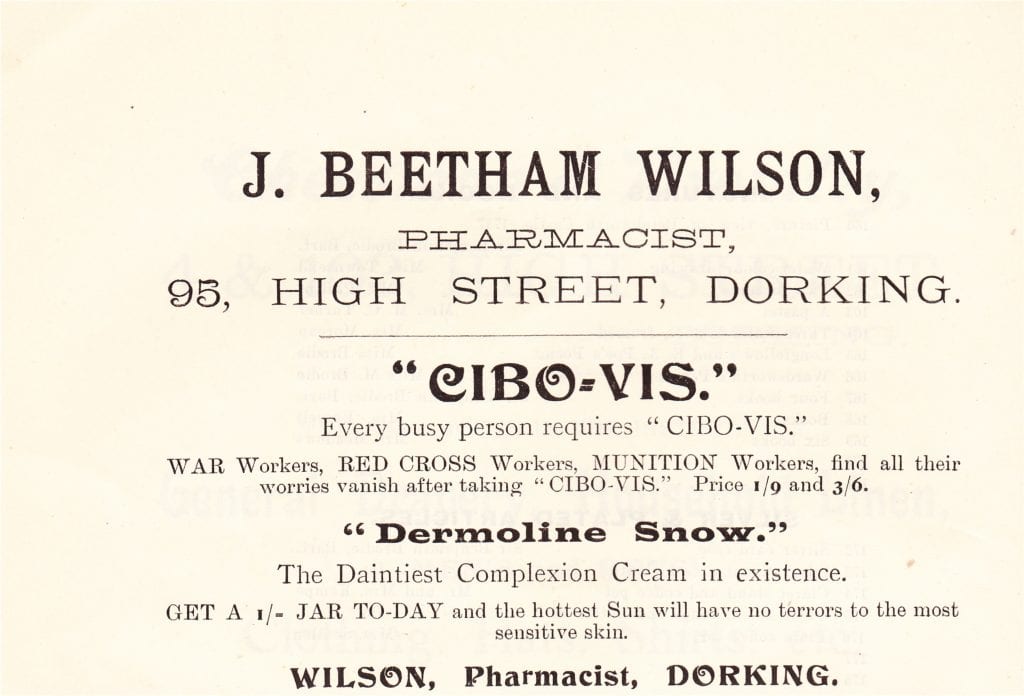

By 1917 the local population was suffering the effects of tiredness and lack of food, creating a a market for such ‘tonics’. Sickness and contagious disease outbreaks in local schools were far higher than in the pre- and post-war years.

When Mr. Wilson was unable to import supplies of atropine for his customers he began growing belladonna in Westcott, but the plants were not ready for cropping to produce the drug until 1918.

Surrey Education Committee allowed children to be taken out of school for berry picking forays to receive an attendance credit. In 1918, children from St. Paul’s School picked 130kgs of berries on Ranmore.